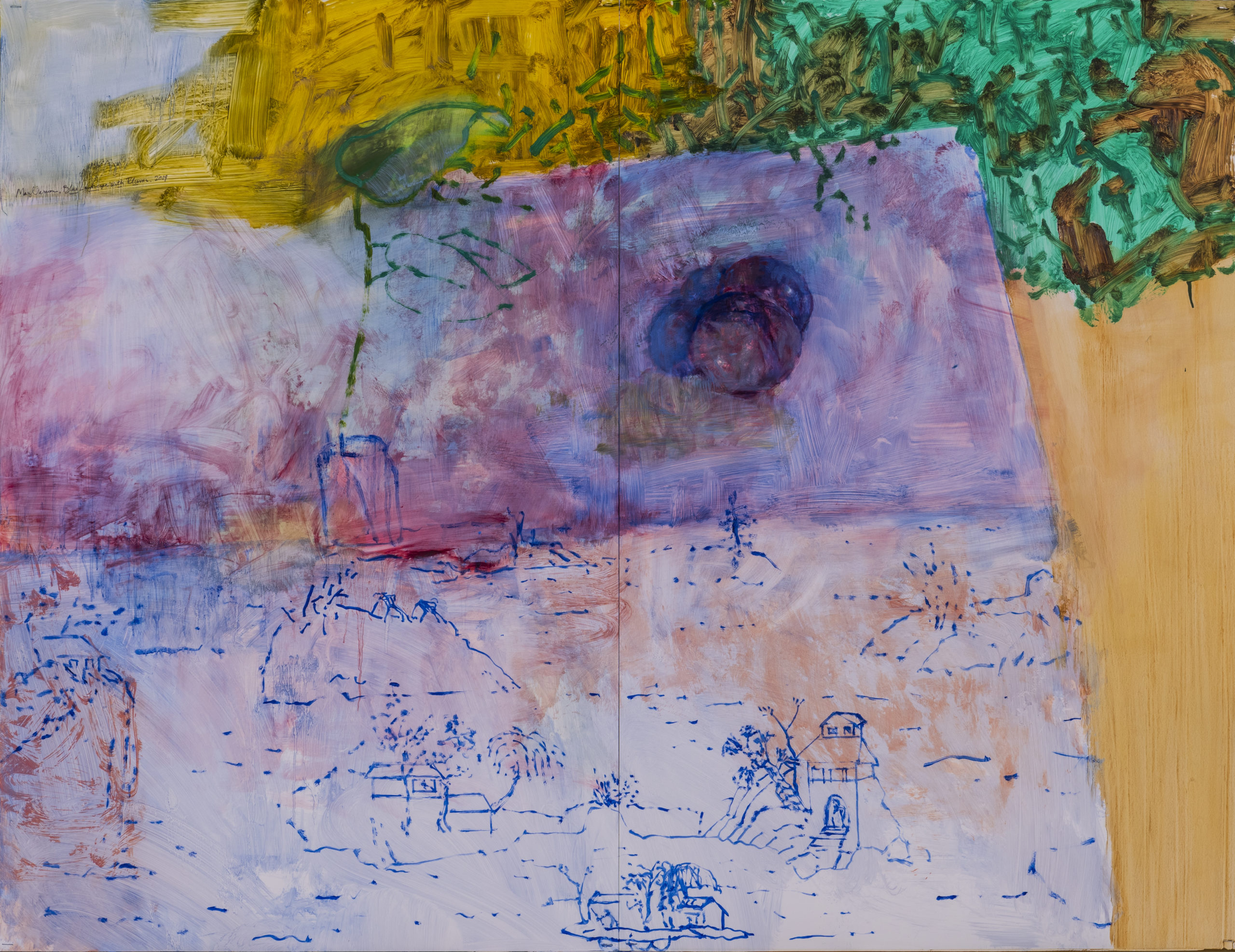

Dust Storm, 2017

The Building for Archives of the United States of America is not big enough, one would think, for the archives. And so, I am sure, it is just the top four floors of a building which may be ten or twenty stories underground. This building is, then, a Roman style cornice on a rectangular, shaft-like form buried in the ground. The muzzle that protrudes from this cornice, the entrance, is a Corinthian temple of eight mighty columns. No flag is flying from the flagpole, no cars, no pedestrians nearby. Perhaps it is the set before the play of history begins.

The horses on the bluegrass farm had a way of matching their shadows to those of the oaks that dotted the land. The long nets of shadow cast by the live oaks slid around the grass in fancy patterns, sometimes resembling characters in The Yellow Submarine, sometimes the worn cloth of old flags. But the horse shadows were as varied as the shadows of puppets skilled tricksters throw on walls. The horses could make steam shovels, Giacometti Walking Men, bar graphs, and Thanksgiving turkeys. They knew it and were proud of their mastery.

Even fake moonlight is moonlight. The spattered pattern of shadow cast in a color unlike the colors of day. Light and dark within darkness make the world intimate. The United States Capitol in this moonlight is sweet as a wedding cake. On this night I am the only visitor, apparently, yet every light is on inside every window, pale yellow against the white light cast by the moon. The sounds of the night and the loneliness of seeing this ought to drive me to seek a place where other people gather. Are they all inside? But I would rather be here, in cobalt and white marble, and the moon and liberty regarding one another.

He is taller than all the distant hills, the man standing in the big freight wagon, holding the reins of the two draft horses. Far away are water towers and trees, and telegraph poles. On the short grass someone has left a white canvas folded, a blanket, a plan, a survey, a shroud, or a cowl. Are they casting fire hydrants? Or are they building the tomb of a Chinese emperor?

Like a bulky matron, sweeping along two identical daughters, the building of the Field Museum in Chicago stalks her ground. Two arms of columns reach out to end in identical pavilions. It is most like a Russian creation aping a French creation aping a Roman creation aping a Persian creation via the tutorial of the Greeks. It is grand lace with a freight of meaning. And the meaning is power. The power is real, no matter how idiotic it is by this late date.

Three beautiful young women were staying at the Bangor Lodge that summer, two brunettes and a blonde. The woods around the lake richly shadowed them in green. The women came down the hill from the lodge, whose awnings were striped in green and white. They sat on the beach on wooden chairs. It was their vacation. All the trees leaned in one direction — to the right.